Digital Divide: Can iPads Close the Gap?

Introduction

Dan Brown conspiracy theories aside, the early Freemasons in the United States relished the Latin motto, “out of chaos comes order.” In a kindergarten classroom at National Teachers Academy on Chicago’s near South side, one teacher is hoping the madness of youngsters freewheeling with iPads can help close the digital divide.

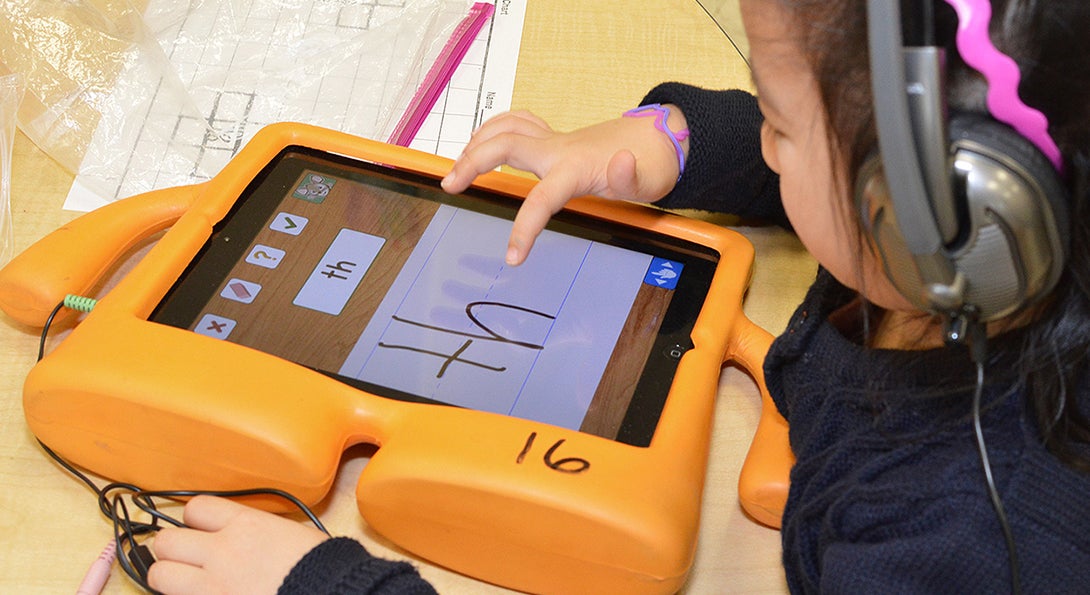

Chaos is neatly defined as 30 five-year-olds with their own iPad. The order part? Thirty kindergartners engaged in individualized learning through technology-assisted differentiated instruction. iPads are remaking the classroom of teacher Carrie Both, an adjunct professor at the University of Illinois at Chicago College of Education in 2007.

Chaos: at the start of an allotted 30-minute period for engagement with the tablet device, the kindergartners descend upon a cart filled with each student’s iPad, each clasped in what appears to be a nuclear bomb-proof day-glo orange rubber cover. iPads are grabbed, headphone cords tangle and tango and students meander back to their desks.

Order: at the tender age of five or six years old, these kindergartners independently start their device. Headphones on, apps engaged, lesson begins. There is only minimal supervision from Both and two teacher assistants.

Each student receives a personalized video via Dropbox from Both, tailored for students struggling with mastering a concept, individual instruction for the day’s lesson or prepping students for the next day’s lesson.

“The iPad has evolved from just a substitute for pencil and paper to really redefining and flipping my classroom,” Both said. “The kids are willing to challenge themselves to do more, things I didn’t even know the apps were able to do.”

Both relies on the iPad to transform her students into content creators. Her students use a book creator app to create books based on what they have learned in class. As students share their work across mobile devices, Both believes her students put more effort into their work knowing their work is public.

Her kindergartners interact with the world at large through Twitter, @NTA110. The tweets are often whimsical—where students are spending the holiday break, for example—but Both says her students want their messages to be seen publicly and engage in greater strategic thinking when forced to consider a public audience.

iPads are also crucial as a catch-up device for students in Both’s classroom. Students still developing writing skills can engage in note-taking by simply talking into their iPad and recording their speech, enabling greater student participation in close reads and Socratic seminars.

“Initially, I’m not a super-techy type of person so it was a struggle, but I see the value in pushing my practice,” Both said. “I really see the value in what the kids are creating.”

Closing the Digital Divide

Before the storm of five-year-olds manhandling iPads, there is the calm of an infant installed in front of a screen.

The earliest of early childhood learners might stare at a TV program or a DVD on a laptop like any adult, but all they see, in the words of wired.com, is a “mesmerizing, glowing box.” The average 12-month old is spending one to two hours daily staring at what amounts to a glorified, pixelated wall.

For parents about to throw their TV off a ledge, hold on. The TV and its digital compatriots have some redemption in store. According to the American Academy of Pediatrics and the National Institute of Health, screen time use can be beneficial for early childhood learning starting at the age of two.

Yet researchers are concerned that passive entertainment screens—TVs, laptops, iPads and smart phones—are leading us into the new age of the digital divide—the so-called “app gap.” More than half of families with mobile devices and incomes above $75,000 have downloaded learning apps specifically for their children. For families with incomes dipping below $30,000, the ratio drops to one in eight.

What the mesmerizing and glowing box will not reveal is that all screen time exposure is not created equal. The passivity of television has a significantly different effect on cognitive development than the interactivity of a well-designed mobile app. As with many of the challenges that impact low-income communities and families, public schools are asked to close this gap. Can an urban school like National Teachers Academy make a difference in traditionally underserved communities?

Bill Teale, PhD, director of the UIC Center for Literacy and professor of curriculum and instruction at the College of Education, says mobile technology can be a tool to develop early childhood literacy skills, particularly in marginalized urban communities, but teachers need resources and professional development to start closing the app gap.

“For three and four-year olds, and certainly for six, seven and eight-year-olds, there are quite a few possibilities,” Teale said. “Technology can be very useful in terms of helping those children with things like foundational skills, developing phonological awareness, learning letters and learning how sounds relate to foundational literacy skills.”

Teale’s research, “Better start before kindergarten: computer technology, interactive media and the education of preschoolers,” was published in the Asia-Pacific Journal of Research in Early Childhood Education. His study found that despite the possibilities for promoting early childhood literacy, most pre-K and early grade classrooms are not utilizing technology for literacy development.

Using grant funding from the U.S. Department of Education, Teale launched workshops for Chicago-area teachers on strategies for incorporating technologies in the classroom. For example, students equipped with digital cameras on a field trip could take pictures and dictate stories that accompany those images. In another instance, the use of iPads could be useful as a touch-screen device for children who may not have keyboard access growing up.

“Increasingly, the early childhood classroom becomes the place where we can begin to level the playing field in terms of digital access,” Teale said. “We’re going to have to end up changing the way we teach technology because technology has changed the way we do business, and business in the largest sense is everything we do in our lives. That means children really need to become comfortable with using these tools.”

As a result, Teale sees an imperative for preschool teachers and early childhood educators, particularly in urban contexts, to develop developmentally-appropriate ways of infusing technology into instruction. Teale says teachers are generally up-to-speed with using social networks, but it is difficult to translate that knowledge into activities appropriate for preschoolers to engage in.

So what does effective early literacy instruction with technology look like? Teale says teachers he studied who succeeded found ways to link to pre-existing technologies, such as e-books, while other teachers used apps that help develop stories designed by young children. The key in both instances is using technology to leverage early language skills.

Teale’s study equipped teachers with two iPads in their classroom. Some urban school districts are going much further—the Los Angeles Unified School District invested $1 billion in 2013 to provide every student with an iPad. The early results from Los Angeles are mixed, but Teale emphasizes the key is not the presence of technology, but teacher ability to integrate technology into curriculum.

“We need to do a better job of giving teachers professional development to get them comfortable with technology,” Teale said. “That is the big mandate for our field. Technology is central to the way in which our society will operate, so it is incredibly important that kids, through their teachers, become comfortable with this in an appropriate way.”