Math and the Connection to Students’ Backgrounds

Is stealing ever acceptable? To student teacher Evan Taylor, this is a math question with an answer that depends on who you ask—and how you ask it.

Taylor’s fifth grade class at Spencer Technical Academy agreed the answer is no—and yes.

When he asked his students if stealing was acceptable in the wake of Hurricane Katrina, the resounding answer was no, unless food or medicine were needed for survival. Then his mentor teacher turned the question around: what if there was an open corner store in the Austin neighborhood with no clerk or cameras?

“A few said they would outright steal, some said they would go into the cash register and one student said he would take food but leave a dollar,” Taylor said. “That’s where math comes into play. You would take all this stuff out of the store but leave one dollar to pay for things? Showing an imbalance, where math can play a conversational piece, helps students see the qualitative measures of what they are doing.”

In 2012, Taylor, BA Urban Education: Elementary Education student, worked with Danny Martin, PhD, professor of curriculum and instruction to study how culture and mathematics intertwine for Black learners. He studied how math practices play out in the lives of young African Americans, from the use of math in track and field to leisure activities popular in Black communities including dominoes and the card game spades. As a student-teacher, Taylor is using his knowledge of how Black students connect math with their everyday lives to broaden their access to math literacy.

When tutoring Black students at Holy Family School on Chicago’s west side, Taylor encountered students struggling to connect with the concept of negative numbers. He knew his students loved to play the video game NBA2K, so Taylor used a video game analogy to demonstrate the concept: if the Bulls are playing the Lakers and trail 72-67, how many points do the Bulls need to equal the Lakers?

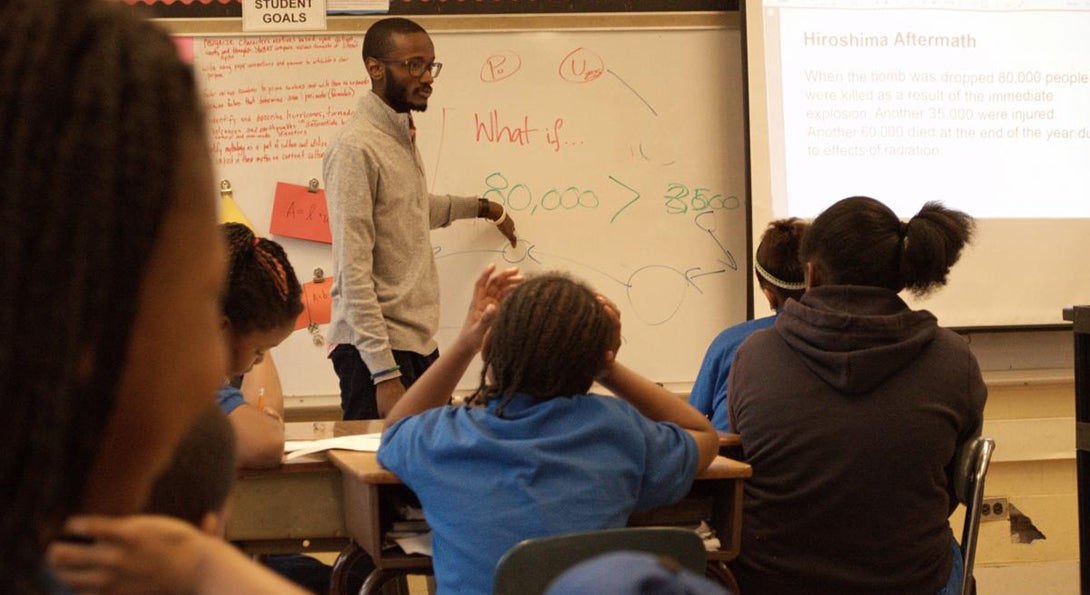

In his student-teaching classroom, Taylor is using math literacy to broaden students’ understanding of subjects outside the math classroom. In a lesson on the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombings, Taylor generated a passionate student discussion on the issue of proportionality: if 2,000 American military personnel perished in the Pearl Harbor attacks, was the U.S. justified in the killing of 135,000 civilians in Hiroshima?

“It’s a matter of opening up your eyes to see the math around you,” Taylor said. “When students understand more than and less than, they can enter a conversation about Hiroshima and Pearl Harbor, they can make sense of where math and social justice begin to walk down the same road.”

Taylor argues access to math skills allows his students to understand the context of their own communities. Sure, an outsider might scoff at students’ indifference towards theft in Austin neighborhood, but Taylor says children are refreshingly honest about the challenges they face in everyday life.

“When you look at how communities are set up in the space of Chicago, how the Austin community was written off as one of the bad checks of the city, you start to examine the economic make-up of a community and why students would steal things,” Taylor said. “Many of us don’t have to think about providing for ourselves or others, but students may be stealing to provide at home. It’s the math and economic situation they are in, but this gets lost in the narrative of mathematics.”

Make no mistake, Taylor isn’t excusing theft. He just wants his students to understand the context of theft. Context in math matters: Taylor argues students know they live in a competitive society and desire personal success, but they know they cannot be the best if the education they receive is unequal. Similarly, he is concerned that STEM fields marketed to Black students frequently focus on blue collar jobs: certified nurse assistants but not registered nurses, mechanics but not mechanical engineers. STEM and math, he says, are taught in ways that do not empower students to positively alter their own communities.